What are game-based assessments?

How about playing a game to figure out your traits and abilities, rather than clicking through a questionnaire? In the last decade, this has increasingly become a possibility. Game-based assessment (GBA) started becoming a thing in the early 2010s, and has continued to draw attention. Many companies – from startups to enterprises – have decided to give the format a shot in their selection processes.

So GBA are what they sound like: psychometric assessments that evaluate traits and abilities by letting the test taker play a game. This is in contrast to conventional psychometrics, where tests are made up of discrete questions that the candidate responds to in a structured format.

GBA and evidence?

Unfortunately, research is still lagging behind industry interest. So understanding where the research is - and if GBA truly delivers on its promises - can help us to know if GBA has a place in an evidence based hiring strategy.

Of course, not all game-like assessments are all that revolutionary. Some test constructors use gaming features more as a ‘spice’ to enhance traditional tests - you might be asked to identify incorrect mathematical problems by shooting the wrong answers down with a water gun, rather than just clicking on them.

At the other end of the spectrum, we find the pure game formats, which represent a new paradigm in test construction. These assessments differ from traditional tests both in what they measure, and how they measure it. These assessments usually consists of playing a game, which is meant to assess both your abilities and the methods you use to attain a certain result.

In comparison to traditional assessments, they generate a massive amount of data – something that could be both a possibility and a challenge. Let’s look into this a bit further.

Richness of data in GBA - friend or foe?

One potential benefit of GBA is that you can assess more things within one single assessment. Indeed, vendors of GBA often claim that each game measures up to 10 traits and abilities each. For example, one GBA exercise could simultaneously assess logical ability, extraversion, and problem-solving style. This has to do with the fact that the game can present the candidate with so many different situations

one GBA exercise could simultaneously assess logical ability, extraversion, and problem-solving style.

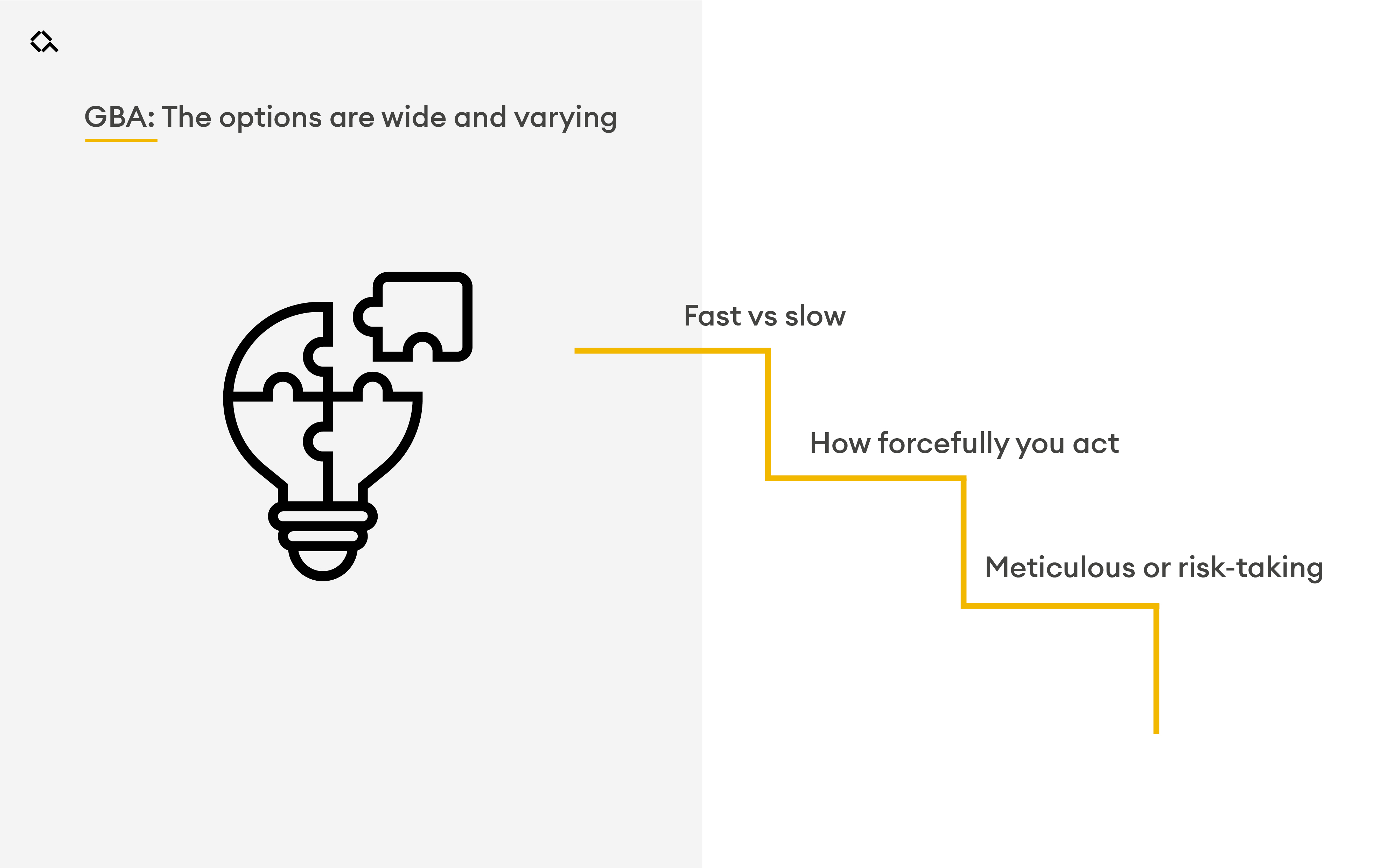

Let’s take a practical example and compare. Say you take a regular logic test. You’re presented with a number of predefined problems to solve. You respond using a set format, e.g. choosing one answer from five different options. The central data points that are collected are your responses to the items - simply put, the most robust data collected is if you get the answer correctly or not.

We might be able to look at a few other things, such as total time spent in the test or time spent per item. But in essence, what we’re interested in is the number of items you answer correctly, and how difficult those items are.

Let’s now say that instead, you do a GBA. Here, you might need to move around in a virtual world to collect information needed to solve a logical puzzle. In each situation, the assessment can track the result you attain. However, it can also track a wide variety of factors related to how you attained that result: how fast or slow you move around, how forcefully you act, whether your search is more meticulous or risk-taking … the options are wide and varied.

This might sound all good – the more data, the better, right? – but there is actually an important downside to this data richness. In order to understand this, we first need to take a look at how a ‘regular’ test is built.

How to build a psychometric test that works

In conventional test construction, you have a very clear idea about what you want to measure beforehand. Each item included is tied to a specific trait (for instance, ‘this question is meant to measure politeness’), and the constructor spends a lot of time and effort making sure that this is actually what gets measured (validity) and that it gets measured right (reliability).

All in all, this makes it possible to back-track what you’re doing, based on items and responses. This, of course, facilitates outside scrutiny: for any given item, the test constructor can be expected to tell you what it measures and how well it does it. They can also be expected to explain how a certain set of responses leads up to a certain overall score.

With GBA, on the other hand, the scoring algorithm is often a lot more difficult to understand.

What exactly are you evaluating in each specific instance? The scoring algorithm is both hard to develop properly and to explain – even to an expert audience. This is especially true when applying machine learning methods such as deep learning.

The massive amount of data generated, and the complex scoring algorithms, also means that psychometric quality risks becoming more volatile: even a small tweak of the test can have a large impact on statistical qualities.

More things are measured - but are they valid?

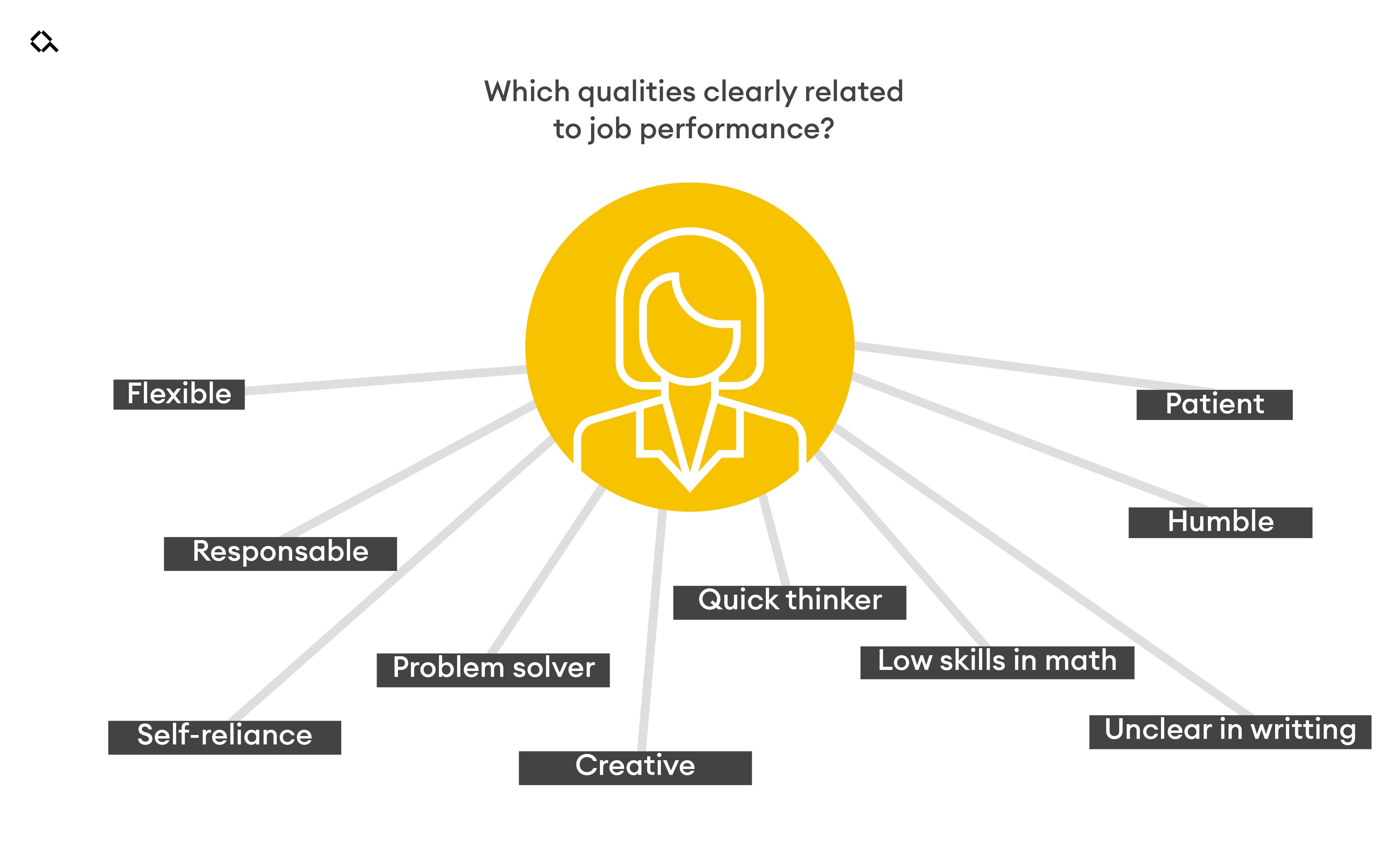

Besides the mere statistical qualities of the measurements in GBA, a bigger question looms: even if the GBA would do a good job at measuring 10 different qualities at once, do we know that all of them are clearly related to job performance?

As we know, predicting job performance is hard – and establishing the predictive capacity of a certain construct takes a lot of time. As a benchmark, logical ability as a predictor of job performance has been scrutinised in hundreds of studies. As an illustration, Salgado and colleagues identified 89 independent studies of this relationship already in 2003 - only in the European context. Since then, there has been ‘impressive’ (Schmitt, 2014) work to further establish the connection.

It’s of course fully possible that most GBAs have full coverage for the predictive power of the things they measure. The tricky thing is that there is often so little information available to judge for oneself.

Could the game format offer less bias and more fairness?

So the richness of the data presents major challenges, and some opportunities. But might the game format also have potential to reduce bias? Some guidance can be taken from the ed-tech sector, where the development of GBA seems to have come a bit further than in candidate assessment.

There are some indications that GBA can better capture those skills and abilities that are ‘invisible’ or hard to detect when evaluated with more traditional assessment methods (de Klerk & Kato, 2017). This might have to do with the game format being more engaging to certain groups of students, who might feel more motivated and hence perform better.

There are also some indications that GBA could reduce test anxiety – a phenomenon that we know might hinder performance. Again, this has to do with the fact that games tend to engage us, allowing us to forget that we’re taking a test.

This could mean that GBA holds promise to further reduce bias and improve fairness in assessment. We know that test results for certain groups can be affected by so-called stereotype threat. That is, for those groups against which there is a negative stereotype when it comes to a certain skill or ability, test results might be affected by the group members’ awareness of that stereotype. This phenomenon has been observed in many different contexts, one example being women and mathematics (Wright & Taylor, 2003).

If GBA can offer a test format that’s less reminiscent of traditional tests, and that also makes you less self-conscious, this could potentially bring a better test-taking experience and a more unbiased evaluation for groups affected by e.g. stereotype threat and test anxiety. So far, however, there is little solid evidence to back this up.

GBA: Are they the future of psychometrics?

So, what do we make of this? As we’ve stated in this blog post, GBA is still in its early days within candidate assessment. However, here are some first conclusions based on what we know.

Research is very much lagging behind on GBA - we need more studies and we need more publicly available data to be able to properly say just how promising it looks.

The immense versatility of GBA is both its strength and its weakness: it opens up a world of possibilities, but it’s also hard to control everything and be sure of what you measure. The potential for reducing bias and adverse impact is one of the most intriguing features of GBA. So far, however, the evidence for such an effect is thin. More research is needed; for now working with validated, evidence-based tests is the only way to know that the data you're collecting is most likely to give you the insights you need for your next hire.